Last year, I wrote a post on the topic of public statues in Manchester, and talked about some of the more intriguing statues around the city. Of course, like any city, Manchester has a multitude of public artworks, and one post was not enough to cover everything I wanted to discuss. My recent walks in the city (including to visit our newest statue) have re-ignited my interest in the topic.

From representation to controversy to international friendships, here are a few more of Manchester’s fascinating statues…

Mrs Pankhurst joins the ranks

In my article last year, I bemoaned the lack of female representation in Manchester’s many public works of art. At the time of the original post, only Queen Victoria was represented. (I’ve subsequently found another woman, Amantine Lucille Aurore Dupin, whom you can read a bit more about below…)

This is alas not an uncommon trend, although Glasgow seems to be ahead of the game with four female statues. (Of course, when we talk about female statues, we mean that of a named, real person, as opposed to an idea or a generalised monument).

Quite surprisingly, despite being voted the Greatest Northerner of all time, there was no statue of Emmeline Pankhurst in her home city until 2018. This was unveiled on 14th December, the centenary of the first votes cast by women in a general election after the passing of the 1918 Representation of the People Act. Nearby Oldham also celebrated the date by unveiling a statue of their own working class Suffragette heroine, Annie Kenney.

Whilst it is good to see moves made to correct the paucity of female statues, it is important that we ensure greater diversity as a whole across public art. How many under-appreciated and oft-forgotten men and women of colour are represented? It was only a few years ago that the UK were erected it’s first statue of a woman of colour: that of Mary Seacole, who nursed wounded soldiers during the Crimean War.

Fryderyk Chopin, and the muse relegated

Across from the John Rylands Library, there is a curious piece of public art. A man sits upon a piano bench, playing to a female listener, whilst figures appear to battle atop the piano and an eagle flies overhead.

The man is none other than composer Fryderyk Chopin, and the woman is his muse and lover Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin, perhaps better known by her pen-name of George Sand. The statue is the work of sculptor Robert Sobocinski, and the piece was unveiled in 2011. It’s intent is to mark the friendship between Manchester and Poland, and the contributions the large Polish diaspora have made to the city.

Chopin himself did visit Manchester and played at the Manchester Concert Hall in 1848, one year before his death. Did George Sand ever visit Manchester? True, she was a friend to adopted Mancunian Charles Hallé, but I could not find any accounts of her time in the city itself.

To me at least, her figure as part of the Chopin statue is a tad questionable in terms of representation. She is presented as a demure figure, listening in awe as Chopin works. However, the real George Sands was a much more interesting figure: a renowned author in her own right, she was admired by Victor Hugo, Fyodor Dostoevsky and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, among others. (Hugo also delivered the eulogy at her memorial) She was active in politics (including as a member of the Paris commune), and opted to dress in male clothing and smoke tobacco, both of which were controversial for a woman in early 19th century France. She conducted numerous liaisons, and is believed to have been the lover of actress Marie Dorval.

Although I cannot know the thoughts and wishes of a woman who died a century before my birth, my educated guess is that she would very much dislike the subservient and docile pose she is portrayed in on this statue.

Humanity (or at least, its statue), Adrift

The statue known as “Adrift” currently occupies the pavement outside Manchester’s Central Libary, although this is not it’s first home. The statue has previously occupied space in both Picadilly Gardens, and round the corner on St Peter’s Square. It also spent a number of years hidden away in storage. I do hope that it’s current dwelling place remains it’s permanent home in the coming years.

(At least it has earned its moniker from its own time “adrift” in the city)

The statue is the work of sculptor John Cassidy, and was completed in 1908. It depicts a family, clinging desperately to a raft and to each other. The plinth at its feet reads:

Humanity adrift on the sea of life, depicting sorrows and dangers, hopes and fears and embodying the dependence of human beings upon one another, the response of human sympathy to human needs, and the inevitable dependence upon divine aid.”

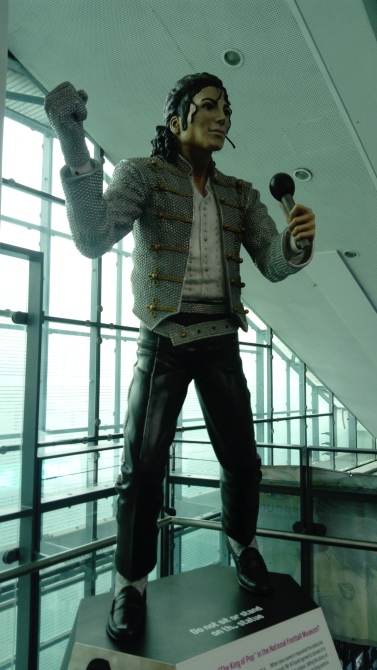

From Fulham controversy to the National Football Museum

In my previous post, I talked about what should happen to the statues of controversial and divisive political figures, such as Confederate generals and slave owners, whose monuments are provoking debate in the United States. It turns out that Manchester itself has at least two controversial statues: one of Oliver Cromwell (moved from the city centre some time ago and hidden away in Wythenshawe Park in the south of the city), and… Michael Jackson? Yes, if ones pop down to the National Football Museum near Victoria Station, one can find a statue of none other than the late King of Pop himself.

Although I do acknowledge that I am perhaps stretching the definition of “public art” when I include a museum exhibit (especially since, from 2019, the Museum has initiated an entry charge due to funding cuts)… but allow me to explain.

Between 1997 and 2013, Fulham F.C. was in the ownership of Mohamed Al-Fayed, who was a friend of Michael Jackson. After Jackson’s death, Al-Fayed commissioned a statue in his honour, which was unveiled outside Craven Cottage in 2011 (Jackson had apparently attended a match there some ten years previously). The figurine was universally loathed by Fulham fans, who labelled it as tasteless and garish. When the club came under new ownership in 2013, the statue was removed. One journey up the M60 later, and it has been in Manchester ever since.

(Incidentally, Fulham F.C. were relegated the following year, with Al-Fayed apparently linking this with the statue’s removal.)

However, if you do visit the National Football Museum, keep your eye out for another statue. It is much smaller, and situated in the front entrance: a commemoration of the 1914 Christmas truce across the battlefields of the First World War.

After all, if anything commendable enough to be immortalised as a statue, it is recognising the humanity in one another even when leaders and governments encourage us to ignore it; and in stretching out the hand of friendship.

Thank you for reading. Perhaps I might revisit this topic in another few months…

Awesome review! I really like the Chopin Statue, the swooping shape reminds me of the one in Warsaw: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chopin_Statue,_Warsaw.

I do like the idiosyncratic nature of some stautes, where a city dweller (or collective) has the disposable income to immortalise a pet subject in stone or bronze and plonk it down.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing the link to the Warsaw statue. It’s interesting who ends up being immortalised as a statue and in what town/city.

LikeLike

Nice post. I like the humanity adrift one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve got a special place in my heart for that one too. Here’s hoping it stays put for a little while!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting selection. I think George Sand just looks like an appendage to Chopin in that statue – i’m sure you’re right that she wouldn’t like it. Not sure about the Pankhurst one: like Mary Barbour in Glasgow she looks unfeasibly slimline compared to real life pictures. My favourite is the Christmas truce.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting selection. Amazingly, I’ve never even noticed the Chopin statue, but will definitely have a look on one of my future visits.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you – statues are one of my obsessions, and I’m always on the lookout for interesting and unusual ones whenever I visit a new city.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Quarterly Digest: January to March 2019 | Wednesday's Child

Pingback: Statues, Statues everywhere! Liverpool Edition | Wednesday's Child