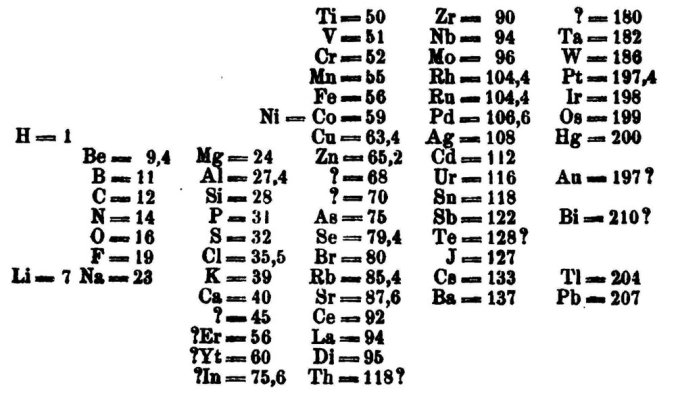

It was upon the sixth day of March in 1869 that a presentation made to the Russian Chemical Society would revolutionise the scientific world. The speaker was an academic from Saint Petersburg University named Dmítriy Ivánovich Mendeléyev. To this group of peers, he unveiled a novel way of displaying the 60 or so known elements (and predicted the existence and properties of many others not discovered for some years).

He had effectively invented the periodic table.

As humans, we attach special meaning to anniversaries, especially those with nice round numbers. Thus, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), in conjunction with UNESCO, have designated 2019 The International Year of the Periodic Table.

For many, the phrase “periodic table” conjures up memories of school science lessons, with antiquated wooden benches, Bunsen burners, and a sun-faded poster on the wall, at least ten years out of date. Perhaps you had to memorise dozens of elements, tripping over boron and bromine, or indium and iodine. Perhaps, like me, you took your chemistry studies further, and learned about some of the more esoteric elements, including the breakdown of their electron orbitals and how to predict reactivity.

Chemistry’s origins stem from very ancient times: from the metallurgy of the Iron and Bronze Ages, to the alchemical experiments of Jabir ibn Hayyan and his contemporaries. Arguably, alchemy and chemistry formally branched off due to the work of Robert Boyle, and his 1661 treatise The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes.

The Periodic Table is more than simply a list of known elements and their atomic weights. It allows chemists to group elements with similar properties together, and to extrapolate and predict the properties of elements yet to be discovered. We can accurately hypothesise how two elements will (or won’t) react together.

In honour of its sesquicentennial, it felt right to delve into the periodic table and look at some of its interesting and important elements.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Hydrogen: the one where it all began

Hydrogen is more than just the first element on the periodic table – it was the first element to be generated by the cosmic energy storm in the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang. From those first hydrogen atoms arose all the elements and matter in the Universe. It fuels the burning of our stars, including our Solar System’s own Sun. Even now, that our Universe consists of antimony, arsenic, aluminum, selenium, and everything else in Tom Lehrer’s Element Song, hydrogen still makes up 75% of the atoms in our Universe.

Hydrogen’s flammability may be the reason life exists on this planet, but it is also incredibly dangerous. The famous Hindenberg disaster is believed to have occurred when a spark ignited the hydrogen on-board the vessel.

Carbon: the backbone of life

If any element can be accused of astonishing diversity, it is carbon. Anything living, from bacteria to fish to mammals to human beings, is made of a complex combination of carbon-based structures. It has an entire branch of chemistry devoted to it’s myriad of structures and uses: organic chemistry.

Carbon-based coal powered the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries (not to mention our ongoing reliance on hydrocarbons and oil). Marilyn Monroe famously described one of its other forms, the diamond, as a girl’s best friend. Or perhaps you prefer it as the graphite in a humble pencil?

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Virtually everything you can name as carbon as an elemental ingredient: soaps, foodstuffs, metal alloys, plastics, paper, medicines… Carbon is everywhere.

However, centuries of reliance on carbon as a fuel has not been kind to our environment. Carbon based gases including carbon dioxide and methane are contributing the climate change beginning to ravage our planet. Disposable plastics, a product of the oil industry, are polluting our seas and landfills, and many prove resistant to degradation. Carbon may have propelled us through centuries of industrial and scientific progress, but as a society we need to reflect on its deleterious effects on the planet, and explore alternates.

Arsenic: From murder to medicine

Word association test: what is the first thing that came to mind when you read the word “arsenic”? I’ll wager that it was poison or a similar sentiment which jumped out. This innocuous white powder has been used as an agent of death in numerous cases of poisoning, both malicious and even accidental. Yet, would it surprise you to know that, in Victorian times, you could pick it up at most chemist’s shops (along with opium, and even cough syrup containing heroin)?

In Victorian Glasgow, one of the most famous criminal cases (still talked about to this day, in fact) was that of the poisoning of Pierre L’Angelier. His former lover, Madeleine Smith, was accused of administering arsenic to him after he threatened to expose their affair. After a sensationalist trial, a verdict of “not proven” was passed, but Smith was never able to escape public scrutiny in Glasgow.

Source: Edinburgh Evening News

A much more widespread case of arsenic poisoning is that of the Bradford sweets poisoning of 1858. Due to the exuberant costs of sugar, it was frequently adulterated with other, cheaper substances, to make something known as “daft”. Confectionery sold to the working classes were usually made with daft instead of the more expensive sugar. Tragically, due to a mix-up at a pharmacy which sold both ingredients, a large quantity of arsenic trioxide was mislabelled as daft and sold to a confectioner. This found its way into a batch of humbug sweets, and over 200 customers were poisoned (20 of whom fatally) as a result. This led to changes in British legislation regarding ingredient adulteration, although it would be two decades before the heavy taxation on sugar was reduced.

In the 1850s, a paper was published in an Austrian medical journal which described a practice known as “arsenic eating” – the consumption of small-but-increasing doses of arsenic, allowing them to build up a “tolerance” to the substance. It was reputed to have “health benefits” – the Victorian equivalent to turmeric and Goji berries and pretty much everything advertised on Gwyneth Paltrow’s lifestyle website.

The existence of arsenic eaters (toxicophagi) is a controversial topic – and how widespread the practice was is now up for debate. Going back to the Madeline Smith case, one theory raised by modern criminologists is that Pierre L’Angelier was a recreational consumer of arsenic, and his death was the result of misadventure rather than murder. I will allow you to draw your own conclusions on the matter…

One might think that medicinal arsenic has been confined to the annals of history… But we do still use it today. It is used (carefully!) as a therapy for a rare variant of leukaemia called APML (acute promyelocytic leukaemia). Sola dosis facit venenum in action.

Radium: the tragic story of the dial-painters

First isolated by Marie Curie in 1902 (some 6 years after she and her husband Pierre had “discovered” the element), radium became popular as a luminous paint for watch-dials, and was added to toothpastes and foodstuffs after being touted as a “miracle cure”. However, even in the very process of working with the element, both Curies suffered the ill effects of radiation. Reportedly, their hands were often raw with radiation burns from exposure to radium.

Concerns about radium’s toxic effects were tragically ignored for decades. The women who worked as dial-painters for the United States Radium Corporation used a technique known as “lip-pointing” to form a fine point on their paintbrushes. Lip, dip, paint. Any rare concerns voiced regarding the safety of doing so were ignored.

The human cost of this would only be realised much later, when many of these women became unwell: anaemia, jaw swelling, fractures, miscarriages… Followed eventually by slow and painful deaths. As their friends, colleagues, and even sisters, began to fade and sicken, their conditions and disquietude was ignored by their employers. Doctors were baffled, ignorant, and powerless to help these women. Eventually, five of them (Grace Fryer, Edna Hussman, Katherine Schaub, Quinta McDonald and Albina Laric) were able to take legal action against the corporation, in a case which set precedents for early workplace health and safety laws in the United States. Their story is the basis of Kate Moore’s excellent and heart-breaking non-fiction book The Radium Girls.

Mercury: The Madness of Hatters

‘You can draw water out of a water-well,’ said the Hatter; ‘so I should think you could draw treacle out of a treacle-well — eh, stupid?’

Once upon a time, mercury (or quicksilver) was believed by alchemists to be able to transmute cheap or base metals into precious gold. Whilst the notion seems ridiculous to us now, one can understand their enchantment with the material.

Mercury is the only metallic element which exists in a liquid form at normal room temperature. It is a beautiful (but toxic) silver liquid, and its droplets form little beads when dropped onto surfaces. (And, having personally broken a mercury thermometer in the lab some years ago, it is a bugger to clean up safely.)

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It has had a myriad of uses down the centuries: it was used in medical devices such as thermometers and early sphygmomanometers (to measure blood pressure). Although our thermometers and BP machines are now digital, we haven’t quite forgotten mercury. Have you ever had your blood pressure checked by a doctor or nurse, and been told your BP is, for example, 125/85? Most times when pressure is measured, we use the unit known as the “Pascal” – but for blood pressure, the unit is known as “millimetres of mercury”, or mmHg.

Another interesting use of mercury was in the millinery industry. The animal skins used to make felt were rinsed in a solution of mercuric nitrate to aid with the matting process. This was known as carroting, due to the orange nature of the solution used. The process continued well into the late 19th century (and, in the United States, until 1934).

However, mercury is a neurotoxin even at small doses. Mercury toxicity is a syndrome called erethism, colloquially known as “mad hatter disease”. Sufferers may exhibit symptoms ranging from headaches, tremor, irritability, and depression, to delirium and memory loss. Chronic exposure can prove fatal. The neuropsychiatric symptoms led to the phrase “Mad as a hatter”.

Interestingly, on re-reading the tea party chapter in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter isn’t described as having any classical symptoms of erethism. Perhaps the Cheshire Cat is right – he isn’t “mad” because of occupational mercury exposure, but because eccentricity is de rigeur for residents of Wonderland.

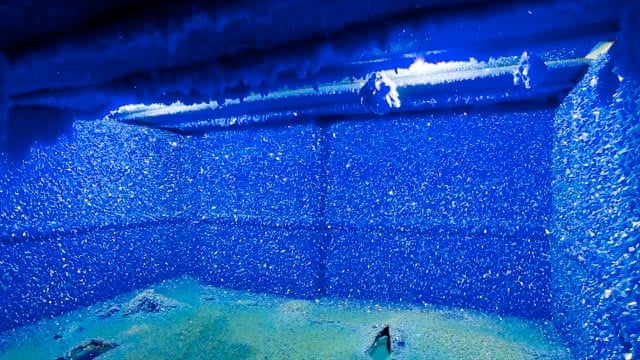

Copper: Crystal Art

Copper sulphate crystals are an enchanting cerulean colour (and always fun to work with). Artist Roger Hiorns, who is known for his alchemical flare, once used this solution as part of a piece known as Seizure. He sealed an abandonned Peckham flat in metal, and poured in over 90,000 litres of copper sulphate solution. After a month, the flat was opened to find beautiful blue crystals deposited over the walls.

Source: The Guardian

It has been 60 years since Tom Lehrer first wrote the famous “The Elements” song. At the time, there were 102 known elements. That number has now reached 118 – who knows how many the periodic table will number by its bicentennial in 2069?

An interesting post about something I didn’t know much about before. The song was the first thing I thought of when I saw your post there!

LikeLiked by 1 person

A one and a two and a… “There’s antimony, arsenic, aluminium, selenium, and hydrogen and oxygen and nitrogen and rhenium…” etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating, I did a couple of OU chemistry courses decades back but haven’t retained much of the knowledge! Madeline features in a couple of GWL walks. In one we point out Pierre’s grave, in another the site of the chemist shop where she purchased arsenic. It’s opposite the MacLellan Galleries which her father designed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, I had no idea about her father was an architect. I believe her grandfather was David Hamilton, who designed Hutchesons’ Hall and the building which now houses GoMA.

LikeLike

Yes, her maternal grandfather so descended from architects on both sides. Her father was called James Smith.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll be keeping an eye out for those GWL walks in that case!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I took a degree in the subject and, like you, haven’t retained much of the knowledge 😂. (Mind you, 40 years is a long time. Just goes to show “use it or lose it”)

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great report! St. Andrews have recently revealed that they found this little beut: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-46904926 probably preserved from all that formaldehyde (and the rest) that was kicking around in the labs back in the day. Faves are rhodium (plates my wedding ring) Caesium (+water = boom), palladium (see Nobel Prize 2010 =oP) hydrogen & oxygen (life giving water and potential rocket fuel to leap from Mars onwards)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some good choices! The St Andrews’ periodic table is fascinating. It’s amazing what you can find in old labs…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Quarterly Digest: January to March 2019 | Wednesday's Child